In the past, societies often recycled construction materials. For instance, in Rome, the stones from the Colosseum were used to build St. Peter’s Basilica. The Incas also reused stones from one project to another. However, today, this practice is rare.

Brandon Clifford, an associate professor of architecture at MIT, notes that we seldom acknowledge how frequently buildings are demolished. He points out, "Today’s architects design buildings under the false assumption that they will last forever. Unfortunately, the reality is that some buildings last only as long as our mortgages, about 30 years, before ending up in landfills."

Clifford adds, "If an archaeologist examines our era, we might be known as the mound builders because we create massive landfills worldwide. Future civilizations might wonder, ‘What were people thinking in the early 2000s when they built these colossal mounds?’"

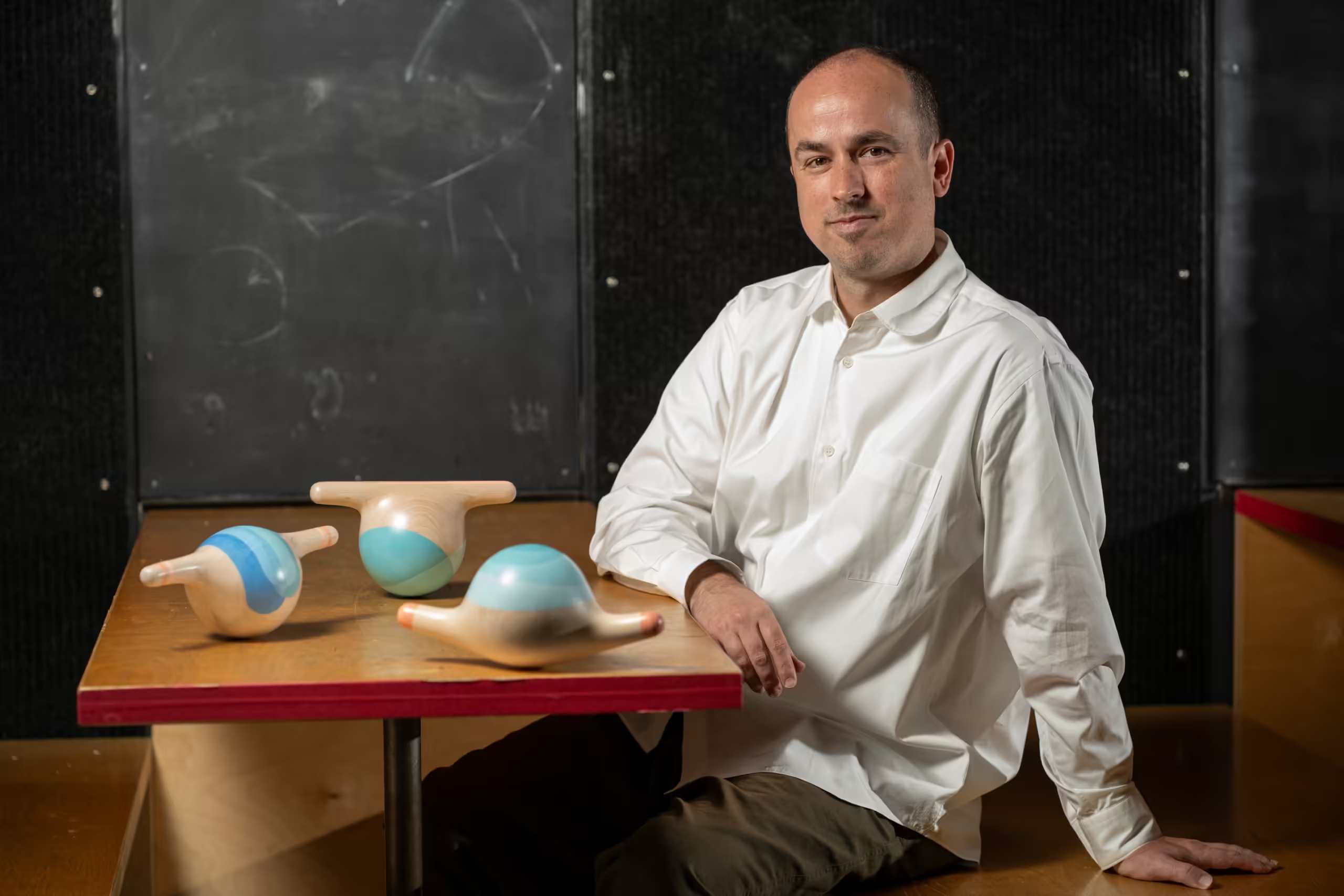

Clifford’s work involves creatively looking back in time to study ancient structures and construction practices to inspire new ones. Recently, his studio, Matter Design, repurposed discarded concrete pieces—from a dairy barn floor, a Motel 6 wall, and a road platform—using digital design and modern cutting tools to create a new wall. If ancient civilizations could repurpose materials, why can’t we?

Clifford explains, "Humans have reassembled random pieces of materials from previous architectural incarnations for millennia, but today, we simply don’t understand the rules." He has designed buildings, written a manifesto on learning from the past, and had his students build and move a megalithic stone around Killian Court.

This article profiles Clifford by piecing together more information about him, aiming to create a lasting narrative—at least for a while.

Leveraging Talent

Almost every architectural work critiques other construction forms. Clifford is candid about this: today’s construction is unsustainable, inefficient, and costly. "The current mode of design and subsequent construction doesn’t work," he wrote in 2017.

In contrast, Clifford’s architectural designs, such as competition entries for the Bamiyan Cultural Center in Afghanistan and the Guggenheim Helsinki, are mindful of material sourcing. His award-winning small project, the Five Fields play structure in Massachusetts, cleverly maximizes its space.

However, Clifford’s career isn’t defined by a single architectural style but rather by a style of architectural thinking. While we are often amazed by ancient architecture, Clifford believes this indicates a lack of creative thinking about how they solved problems. Ultimately, he seeks to leverage the talents around him to reshape our building habits.

"In our lab, we consider our work successful if it challenges your view of the broader discipline," says Clifford, who secured his position at MIT this year.

Space Odyssey

Clifford’s father was an astronaut. Rich Clifford served in the military, joined NASA, and participated in three space shuttle missions in the 1990s. "I grew up in Houston, surrounded by the space industry," Clifford recalls. He lived next to astronaut John Young, one of the 12 people to walk on the Moon and co-pilot of the first space shuttle flight in 1981.

Rich Clifford was diagnosed with Parkinson’s disease before his last shuttle flight and passed away in late 2021. Brandon Clifford reflects on his father’s trajectory and its influence on his own.

"I work on prehistoric, gravity-laden human contributions to Earth, while my father explored space," he says. "But we’re both explorers, in very different ways."

In some ways, NASA reminds Clifford of his current employer. "NASA is a fascinating place for cross-pollination of ideas," observes Clifford. "It’s a balance between military and public images of space. The space industry has always generated thought-provoking ideas about humanity while being scientifically rigorous. I consider MIT on par with NASA in that regard."

Stones and Civilization

Clifford graduated from Georgia Tech in 2006, where he studied architecture with a focus on digital fabrication. He pursued graduate studies at Princeton University as the real estate market collapsed. "Every classmate of mine was losing their job in architecture," Clifford recalls.

During his graduate studies, he revisited digital fabrication. Then one day, MIT architectural historian Mark Jarzombek visited Princeton for a lecture.

"He said you can tell a civilization is doing well if it precisely carves stone," Clifford explains. "That moment changed my career, and since then, I’ve been studying stone architecture." Incidentally, we don’t do much stone carving today either.

Clifford began thinking historically and globally. A common narrative is that architecture emerged from shelter-making. Yet, from Egypt to Easter Island, many societies often refined their building techniques for other purposes.

"When you look at prehistory, the pyramids, Stonehenge, the moai of Easter Island, the Incan polygonal masonry structure, none of them are shelters," Clifford explains.

Exploring these structures reveals how societies maximized their resources. When the Incas recycled stone blocks for walls, they only cut the top part to fit each block into the new structure. The Greeks would cut the bottom part. But both optimized their resources and labor. Ancient practices contain valuable insights.

What You Don’t Know Can Help You

Yet, we don’t know everything about ancient buildings. For Clifford, this is a feature, not a bug.

After all, if there are mysteries about past architecture, we have the opportunity to think creatively about them. Given 12 hypotheses about how Stonehenge was built, 11 might be historically inaccurate—but several could contain intriguing ideas.

"My work is often misinterpreted as experimental archaeology," Clifford explains. "But as an architect, I’m interested in the future. I’m not trying to prove anything about the past. I’m just trying to extract bits of knowledge or find alternative ways of thinking about past constructions that can change how we think about the future. If a theory changes how we do something, it’s still useful."

Make a Megalithic Move

When outsiders reached Easter Island in 1722, an obvious mystery was how the island’s massive statues were transported. The islanders claimed the moai had "walked" to their locations, which seemed like a fanciful myth.

But in 2011, archaeologists Terry Hunt and Carl Lipo proposed that Easter Island’s statues were transported upright, with people using ropes to rock the statues from side to side while rotating them forward. Thus, the statues could have "walked," even if not everyone immediately accepted this hypothesis.

Clifford, who arrived at MIT in 2012, co-taught a course with Jarzombek in 2015 that included a group project: students built a 16-foot fiberglass-reinforced concrete megalith and figured out how to transport it around Killian Court with ropes. They named it the McKnelly Megalith. The course had a teaching assistant, Carrie Lee McKnelly, whose parents had tragically passed away, so the name was in their honor.

One key to the McKnelly Megalith’s mobility was its curved shape. Since the center of gravity isn’t in the middle of the structure’s form, it’s easier to pivot and rotate. Easter Island’s moai also use this design principle. The MIT course wasn’t the first test of moving a megalith with a rope—Hunt and Lipo did it in Hawaii—but it reinforced the method’s viability.

"Honestly, this is the kind of thing celebrated in MIT culture," says Clifford. "Let’s make a big megalithic move."

And Float

In 2016, Clifford and his students doubled down on megaliths with the Buoy Stone, a massive pear-shaped piece of fiber-reinforced concrete they moored in the Charles River outside Killian Court for a few months.

The Buoy Stone was built for the "Moving Day" project, a celebration of the 100th anniversary of MIT’s move from Boston to Cambridge. The stone explored transporting megaliths over water—like many pieces of Stonehenge. In this case, the Buoy Stone was towed on the water horizontally, then, once stationary, partially filled with water and tilted vertically. The object also sparked much local curiosity.

Clifford again: "We had no signage indicating what the Buoy Stone was. With megaliths, that’s part of the mystery: why is this thing here? A giant stone miles from the nearest quarry is an intriguing artifact. People in Cambridge still tell me, ‘I run along the Charles River and wondered what that weird thing was.’ It was a fun project because it was a celebration of MIT."

The Buoy Stone didn’t address a historical debate as directly as the McKnelly Megalith, but it may have contemporary applications, perhaps in barrier-type structures, and was an exercise in creative design.

"At MIT, students are very open and receptive to thought-provoking ideas," says Clifford. "They want to think differently."

Colossus and Cosmos

Clifford isn’t the only MIT faculty member studying ancient building techniques; others include Jarzombek, John Ochsendorf, Admir Masic, and more. But he has carved out his niche in the area and is currently working on a new book project about his explorations, tentatively titled "Colossus and the Cosmos." He has given a TED talk and won the American Academy in Rome prize, among other accolades.

This will be Clifford’s second book. His first was his original 2017 volume, "The Cannibal’s Cookbook," with the term "Cannibal" alluding to recycling building materials, while the "Cookbook" part refers to the idea that there are recipes for doing so.

And although there are already proponents of "circular construction," a greater reuse of building materials, Clifford believes the concept needs wider dissemination.

"The way architecture is set up today doesn’t allow for that," says Clifford. "We have no way to reincorporate materials. Much of the reception of the first book came from architecture students exploring design. I hope the next impact will be on the building sector, finding ways to automate this process."

Creative Enterprise

Tenure can allow professors to pursue independent projects, although Clifford, for his part, has never needed much encouragement in that regard. A nuance in Clifford’s career, however, is that even though he has followed his path, it has involved many collaborations.

"I have the best colleagues I can imagine, and I also consider my MIT graduate students as colleagues," says Clifford.

He adds, "I’ve never completed a project alone. I had this idea, before starting architecture school, that an architect just sat at a drafting table and designed buildings, the lone genius thing. But every project I’ve done is a collaboration with someone who knows something different. I realize there’s so much I don’t know."

Once again, there’s this idea that gaps in our knowledge are an opportunity. We will never know everything about ancient buildings, but nevertheless, as Clifford notes, "The question is, ‘What do you need to know about something to change your way of thinking about the future?’ That’s where the value lies."