Coastal homes being swept away by the sea due to erosion and powerful storm surges are becoming increasingly common as climate change leads to rising sea levels and more intense storms. In the United States alone, coastal storms caused $165 billion in damages in 2022.

A recent MIT study suggests that protecting and enhancing salt marshes in front of protective seawalls can significantly safeguard certain coastlines at a cost-effective rate. These findings are detailed in the journal Communications Earth & Environment by MIT graduate student Ernie IH Lee and civil and environmental engineering professor Heidi Nepf. Nepf emphasizes that coastal marsh restoration is not just a desirable action but also economically viable. The study reveals that the wave-dampening effects of salt marshes allow for the construction of lower seawalls, reducing construction costs while maintaining storm protection.

Nepf highlights that even small marshes, just a few dozen meters wide, can provide substantial benefits, offering hope that these insights could be applied in areas where saving a small marsh might have been previously deemed unworthy. The study demonstrates that these marshes can make a significant difference financially.

While previous studies have shown the benefits of natural marshes in mitigating devastating storms, Lee points out that these often focus on large marshes spanning several hundred meters. This study aims to show applicability in urban settings with limited marsh availability, where existing gray infrastructure like seawalls is already in place.

The research utilized computer modeling of waves across various shoreline profiles, considering the morphology of different salt marsh plants—their height, stiffness, and spatial density—rather than relying on an empirical drag coefficient. This physical model of plant-wave interaction allowed for examining the influence of plant species and seasonal morphological changes without needing to calibrate vegetation drag coefficients for each condition.

The cost-benefit analysis was based on a simple measure: how much could the height of a seawall be reduced if accompanied by a certain amount of marsh? Other valuation methods, like including the value of real estate potentially damaged by flooding, vary significantly based on asset valuation during floods. Lee explains that they use a more concrete value to quantify the benefits of salt marshes, equating to the equivalent seawall height needed for the same level of protection.

The study used models of various plants, reflecting seasonal differences in height and stiffness, and found variability in their wave attenuation effectiveness, but all provided useful benefits.

To validate the simulations, Nepf and Lee examined local salt marshes in Salem, Massachusetts, where restoration projects are underway. Their model showed that a healthy salt marsh could offset the need for an additional 1.7 meters (about 5.5 feet) of seawall height, based on a pedestrian safety wave overtopping rate.

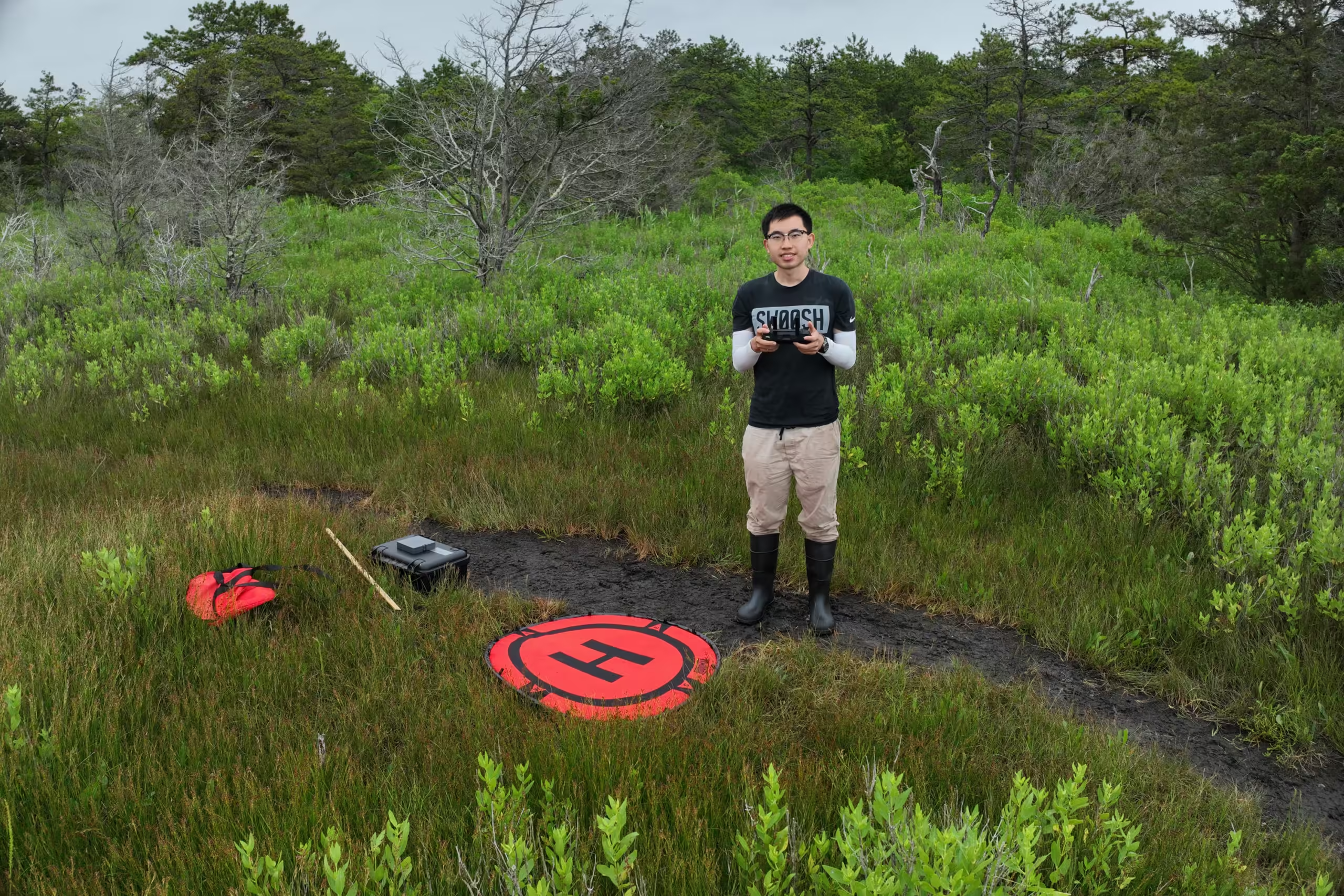

However, gathering real-world data necessary for marsh modeling, including maps of salt marsh species, plant height, and density, is labor-intensive. Lee is developing a method using drone imagery and machine learning to facilitate this mapping. Nepf states this will enable researchers or planners to assess a marsh area and determine its flood reduction value.

The White House Office of Information and Regulatory Affairs recently issued guidance for evaluating ecosystem services in federal project planning, but specific methods for quantifying value are often lacking. This study addresses that need, says Nepf.

The Federal Emergency Management Agency also has a cost-benefit analysis toolkit, notes Lee. It provides guidelines for quantifying environmental services, and this paper’s novelty lies in quantifying the cost and protective value of marshes. This is one application policymakers might consider for assessing the environmental service values of marshes.

The software for environmental engineers to apply to specific sites is available online for free on GitHub. "It’s a one-dimensional model accessible to a standard consulting firm," Nepf explains.

"This paper offers a practical tool to translate marsh wave attenuation capabilities into economic values, potentially aiding policymakers in adapting marshes for nature-based coastal defense," says Xiaoxia Zhang, a professor at Shenzhen University in China, who was not involved in the work. "The results indicate that salt marshes are not only environmentally beneficial but also cost-effective."

The study "is a very important and crucial step in quantifying the protective value of marshes," adds Bas Borsje, an associate professor of natural flood protection at the University of Twente in the Netherlands, who was not involved in the research. "The most important step missing now is how to translate our findings to policymakers. This is the first time I know policymakers are informed quantitatively about the protective value of salt marshes."

Lee received support for this work from the Schoettler Scholarship Fund, administered by MIT’s Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering.