A growing number of Americans struggling to pay for household energy live in the South and Southwest, reflecting a climate-driven shift from heating needs to air conditioning use, according to a study by MIT. The recently published study also highlights that a significant U.S. federal program providing energy subsidies to households, which allocates lump-sum grants to states, does not yet fully align with these recent trends.

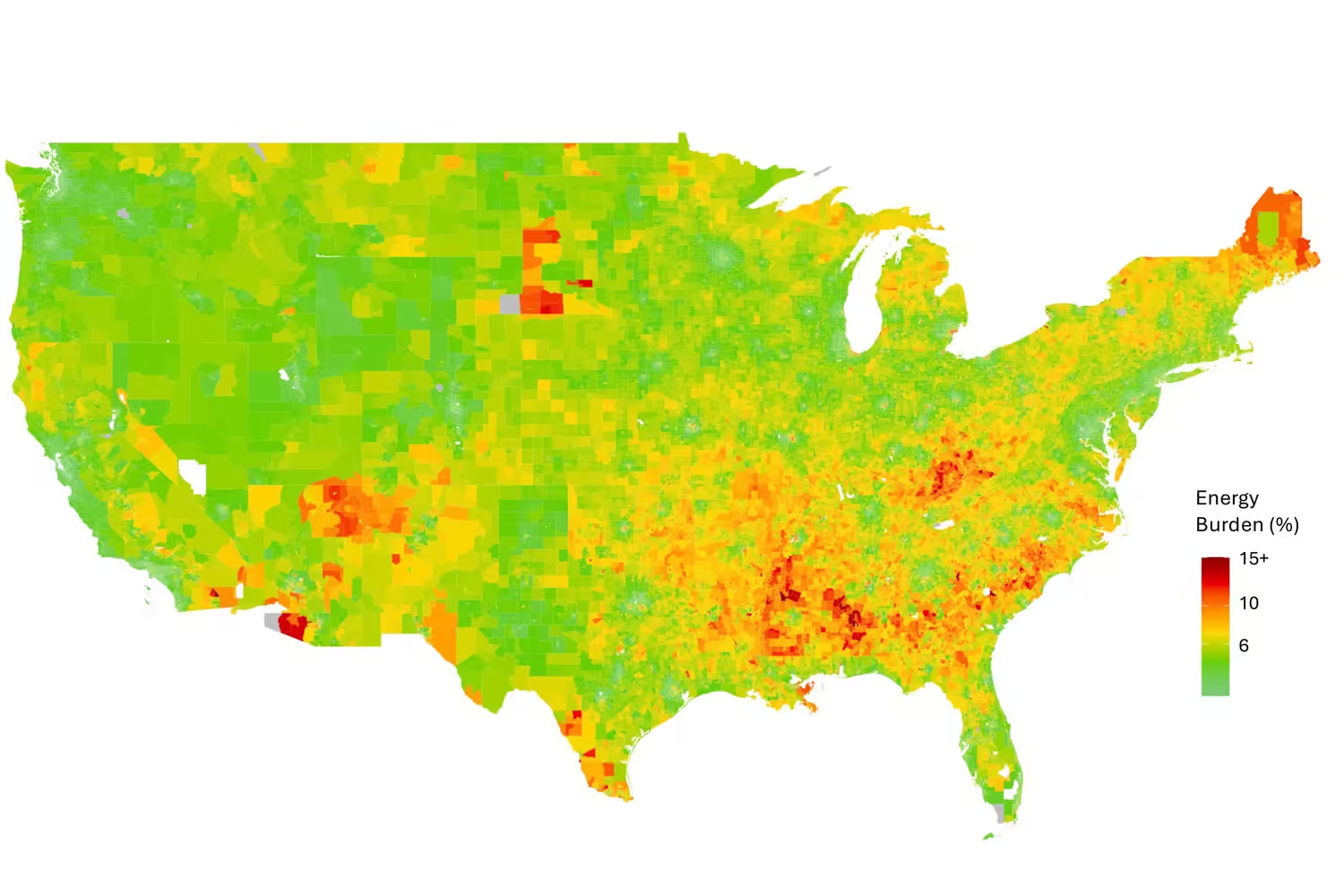

The research evaluates the "energy burden" of households, which is the percentage of income required to cover energy needs, from 2015 to 2020. Households with an energy burden exceeding 6% of their income are considered to be in "energy poverty." With climate change, rising temperatures are expected to exacerbate financial stress in the South, where air conditioning is increasingly necessary. Meanwhile, milder winters are expected to reduce heating costs in some colder regions.

"From 2015 to 2020, there is an overall increase in the burden, and we also see this shift towards the South," says Christopher Knittel, an energy economist at MIT and co-author of a new paper detailing the study’s findings. Regarding federal aid, he adds, "When you compare the distribution of the energy burden with where the money is going, it’s not very well aligned."

The paper, "U.S. Federal Resource Allocations Are Mismatched with Energy Poverty Concentrations," is published today in Science Advances. The authors include Carlos Batlle, a professor at Comillas University in Spain and a lecturer at the MIT Energy Initiative; Peter Heller SM ’24, a recent graduate of the MIT Technology and Policy Program; Knittel, the George P. Shultz Professor at the MIT Sloan School of Management and Associate Dean for Climate and Sustainability at MIT; and Tim Schittekatte, a lecturer at MIT Sloan.

A Scorching Decade

The study, based on graduate research conducted by Heller at MIT, employs a machine-learning estimation technique applied to U.S. energy consumption data. Specifically, the researchers sampled about 20,000 households from the U.S. Energy Information Administration’s Residential Energy Consumption Survey, which includes a wide range of demographic characteristics, as well as geographic and building type information. Using data from the U.S. Census Bureau’s American Community Survey for 2015 and 2020, the research team estimated the average household energy burden for each census tract in the lower 48 states—73,057 in 2015 and 84,414 in 2020.

This allowed the researchers to track changes in energy burden over recent years, including the shift towards a higher energy burden in southern states. In 2015, Maine, Mississippi, Arkansas, Vermont, and Alabama were the five states (ranked in descending order) with the highest energy burden among census tracts. By 2020, the situation had shifted somewhat, with Maine and Vermont dropping off the list and southern states experiencing a heavier energy burden. That year, the top five states, in descending order, were Mississippi, Arkansas, Alabama, West Virginia, and Maine.

The data also reflect an urban-rural shift. In 2015, 23% of census tracts where the average household lived in energy poverty were urban. This figure dropped to 14% in 2020.

Overall, the data align with the picture of a warming world, where milder winters in the North, Northwest, and Western mountains require less heating fuel, while more extreme summer temperatures in the South necessitate increased air conditioning.

"Who is going to be most affected by climate change?" asks Knittel. "In the U.S., unsurprisingly, it will be the southern part of the country. Our study confirms this but also suggests that the southern U.S. is the least equipped to respond. If you’re already burdened, the burden gets heavier."

A Shift for LIHEAP?

In addition to identifying the changing energy needs over the past decade, the study also highlights a longer-term shift in U.S. household energy needs, dating back to the 1980s. The researchers compared the current geography of U.S. energy burden with the assistance currently provided by the federal Low Income Home Energy Assistance Program (LIHEAP), which dates back to 1981.

Federal aid for energy needs actually predates LIHEAP, but the current program was introduced in 1981 and updated in 1984 to include cooling needs such as air conditioning. When the formula was updated in 1984, two "hold harmless" clauses were also adopted, ensuring states a minimum amount of funding.

Nevertheless, the parameters of LIHEAP also predate the rise in temperatures over the past 40 years, and the current study shows that, relative to the current landscape of energy poverty, LIHEAP distributes relatively less of its funding to southern and southwestern states.

"The way Congress uses formulas established in the 1980s keeps the funding distribution roughly the same as it was in the 1980s," observes Heller. "Our paper illustrates the evolution of needs that has occurred over the decades since."

Currently, LIHEAP would need to be quadrupled to ensure that no American household faces energy poverty. However, the researchers tested a new funding model, which would first assist the most disadvantaged households nationwide, ensuring that no household has an energy burden exceeding 20.3 percent.

"We think this is probably the fairest way to allocate the money, and by doing so, you now have a different amount of money that should go to each state, so that no state is worse off than others," says Knittel.

Even though the new distribution concept would require some reallocation of grants among states, it would aim to help all households avoid a certain level of energy poverty across the country, in an era of climate change, global warming, and evolving energy needs in the U.S.

"We can optimize where we spend the money, and this optimization approach is an important thing to consider," says Knittel.